1. Strategy

The first prerequisite for mastery in Scrabble is a fundamental grasp of strategy.

What is strategy?

Strategy is the formulation of a plan implemented by employing appropriate tactics. As in chess, the scope of Scrabble strategy includes the opening moves, the mid-game phase and the endgame.

The Opening Move

Is going first an advantage?

There is an adage in Scrabble that says 'the player going first will win 54% of the time - all other things being equal'. Going first allows you to control the board - you determine whether your move will be horizontal or vertical , expose a premium square or a double word file, close or open the board.

Should you play the opening move horizontally or vertically?

I actually start my first move vertically - but I rarely find an opponent who does the same. Since we are used to reading in a linear fashion it is slightly disconcerting to deal with a column of letters first up. On the other hand it is easier to find eight-letter words horizontally. The British Champion Allan Simmons once suggested you should alternate the direction of your opening move depending on the quality of your opponent and the structure of the word.

Should you always avoid exposing the Double Letter Squares around the centre square?

As a rule, yes, avoid giving your opponent an easy 50 or 60 points. However, if you yourself hold two power tiles (like the Z and the J) and a couple of O's you might consider exposing a Double Letter Square as a set-up play.

Extensions to the Triple Word Squares after the opening move

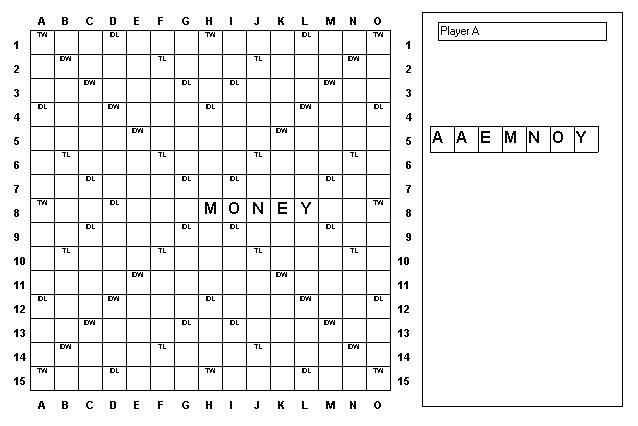

Look at the board situation below. Say you wanted to start the game with the word MONEY. You could play it starting with the M on the centre square and the Y on the Double Letter Square at H12 or 12D. Seems safe enough, doesn't it? But what about words extending to the Triple Word Square like MONEYBAG, MONEYMAN, MONEYMEN or the unusual MONEYERS?

The MONEY example shows how some common words can have surprise extensions to a Triple Word Square. In fact, just about wherever you play the word it can be extended to a triple word square (MONEYBAGS, MONEYMAKER, MONEYMAKING, MONEYLENDERS, NONMONEY, COMMONEY and BALDMONEY).

With this rack maybe you'd be better off getting rid of your MONEY problems by playing YEOMAN instead!

Other examples of what the French call Benjamins are DIS-QUIET, SUB-ZONES and CON-JOINS. A knowledge of these surprise extensions will help you to develop your skills in "three-upmanship".

Should you ever open a Double-Double lane?

A five-letter opening word can provide an opportunity for a bonus linking two Double Word Squares and receiving quadrupled points. The aggressive player will happily open up a double-double lane confident he will have the tiles to go there next time. If it means turning over more tiles and improving your rack balance don't be too chary of the double-double on your opening move.

Should I go for tile turnover or rack control in the opening move?

In the North American tournament scene in the 70's and 80's tile turnover was almost a holy cannon of play. The argument ran 'Turning over more tiles gets me closer to the blanks and esses.' True, but playing away TRAIN on your first move (leaving V-E) may be less advisable than turning over no tiles, dumping the V and retaining the promising R-E-T-I-N-A. Finally picking up an S is not much good if you only have a "bunch of junk" to go with it. However, in recent years experts (and computer simulations) have recognised the competing claims of rack control and tile turnover. It all depends on what's on your rack.

Following a decision tree

I find it helpful to approach my opening rack with a sequence of specific questions:

Do I have a bonus? No. Can I set up an unusual hook my opponent may not know? No. Do I go for tile turnover or rack control here? Tile turnover. Can I set up a Double Letter Square for one of my "power tiles"? No My choices of word are x y or z. What are the advantages and disadvantages of each move?

Should I ever pass or play a phoney hoping my opponent will give me a letter for an eight?

At expert level this is rare. If you have a fruitful Non-go (a promising combination which doesn't quite make a bonus) on your rack it is better to dump tiles than pass. Otherwise your opponent will simply use the occasion to exchange letters and improve his rack and you have lost the opening momentum. Against an unwary opponent you might take a punt and play a plausible-sounding non-go like MALTIES knowing that if it is challenged off there are 38 eight-letter words formable from this combination should your opponent be foolish enough to give you any one of the fourteen add-on letters.

Replying to the opening move

We saw that the player going first wins 54% of the time. What about if I am replying to the opening move?

The good news is that the player going second is more likely to play the first bonus of the game (since he has eight- letter possibilities as well).

Strategically, the player replying will probably be obliged to open up DWS lanes or the files leading to a TWS. If you must leave floaters or open squares (like the hot DLS four squares away from a TWS) try and make an awkward tile like a V or a C rather than an R or T, a U or I instead of an E A or O.

To test your skills try the Opening Practice Session and see how the experts might deal with some typical opening racks.

Middle Game

After the first two or three moves the board has generally defined itself and player have a feel whether it's going to be a "nip and tuck" type of game with a ladder of tiles blocking one side or a wide open game with plenty of "floaters" and scoring opportunities. Both players are hunting for that first bonus word and when it comes it generally dictates strategy into the mid-game with the player behind trying to score and/or balance his rack before the opponent lands another bonus - like two boxers waiting to score a knockdown early in the contest.

As in chess, mid-game strategy is more intuitive, less scientific than the endgame. Good players often manage the board and direct the traffic of the tiles to their own advantage. Robert Felt and Joel Sherman are the best players I've seen at doing this - they have an uncanny instinct for which part of the board their opponents are likely to go. On the other hand, when you're playing less talented players openings will often just pop up everywhere. Later on we will look at board management and the techniques of closing and opening boards, making set-ups, feinting and shepherding.

In the meantime take a look at some typical mid-game situations and see how you would handle them.

20 Tactical Tips

- When you are well behind open up the board, if you are well ahead keep it closed.

- If you have a good rack play more aggressively; if you have a poor one, play defensively.

- If your opponent is stronger than you (both in word knowledge and strategic skill) play a tight game. If you are the stronger player try and keep the board open to take advantage of your superior word knowledge and bonus power.

- Take out floaters if you are ahead; create floating letters if you are behind.

- Avoid exposing double-double lanes or triple-triple files - unless you are 150 or more behind and desperate or your great tiles allow you to play aggressively.

- If you play into a triple word file try and place an awkward letter there - a V or a Y - rather than flexible letters like R, N or T so as to minimise the nine-timer.

- Try to interpret the intention of your opponent's moves. For example, playing away a single tile may mean he is close to a bonus play, if he makes a low-scoring word with an S it may mean he has another one or opening up a TLS next to an I could mean he has the X or the Q.

- Play the board not the rack - don't go chasing bonuses and forget the state of the game.

- Watch out for open premium word squares (particularly spots for the J, Q, X, and Z going both ways across a Triple Letter Square.)

- When you are behind try and open diversion spots and feints - say a TWS to take attention away from the last available bonus lane.

- If you need a bonus play to catch up make sure you keep two or three spots available for your word when you get it.

- Define the hot spots for each board situation - areas of the board which yield you (or your opponent) a high or decisive score.

- Identify the hot tiles (on the board or still to be played) such as Q X J or Z, a blank or the last E - which may decide the outcome of the game.

- Force your opponent to play a bonus word in a position which gives you counterplay. For example, you might block one of two free bonus lanes obliging your opponent to use Row 14 thus enabling you to sextuple your Z from H12 down to the TWS at H15.

- If your opponent opens up a TWS file and you can't use it effectively, consider opening another.

- Look for set-up plays Use set-ups to give yourself a hook for a bonus, extend to a TWS, optimise the value of a high-scoring tile or (in the endgame) to extend your winning margin

- Remember to minimise your opponent's scoring opportunities and maximise your own. Very often your opponent will score well off a tile "Because you put it there".

- Play the tournament - not the game. Often players will lose interest in a game when well behind when they should be optimising spread in events where the final places are determined by total margins.

- Play the game - not the opponent. Players often forget tactical considerations when playing an ostensibly stronger or weaker player.

- Never give up. Even desperate situations can turn around dramatically. There was never a more desperate situation than the famous fourth game of the final of the 1993 World Scrabble' Championships played in the Plaza Hotel , New York between Englishman Mark Nyman and Canadian Joel Wapnick. Trailing by 2 games to 1 in the best of five series Mark clawed his way back from 181/355 down to win by nine points. He then went on to clinch the title in the fifth game.